Alumni article: Reflections on the KCL Movement Workshops

As part of the Erasmus ARTHEWE project, Education masters King’s College London graduate, Niamh Carey discusses her experiences of contact improvisation workshops, embodiment, and how the two relate to her profession as an educator for adults with learning disabilities and autism.

It’s 7pm on a dark October evening, and I am being blindly led by a stranger around an exhibition space. My eyes are closed; the only choice I have is to trust and follow my partner as she deftly navigates the room on my behalf. I hold her shoulder as she quickens her pace, dips down to the floor, makes unexpected twists and doubles back: the whole experience is perplexing, nerve-wracking and fun in equal measure.

This might all sound a bit like certain team-building exercises that elicit (perhaps deservedly) an eye roll or two from reluctant colleagues, but clichés often contain a whole lot of truth, and with this exercise I’m fast learning about the power of communication and understanding through an idea called ‘embodiment’. Over the next six weeks, I will come to fully understand and embrace the meaning of that term.

As a recent King’s masters graduate, I was invited to participate in ARTHEWE, an international Higher Education project that seeks to develop ‘multiform pedagogical approaches and art-based methods in the field of arts and health’ (TURKU UAS, 2022). In short, it looks at ways that educators can incorporate creative methods into their teaching. As part of ARTHEWE, the Faculty of Social Science & Public Policy at King’s facilitated a series of movement workshops for education, dentistry and medical students, focusing on how we can build skills such as leadership, trust and empathy through dancing and moving together in the same space (and, thankfully, with our eyes open for the most part).

The first workshop began with participants sitting tentatively in a circle. We were mostly strangers to each other, and none of us really had a clear idea of what we had signed up for. Our collective apprehension was tangible; the awkwardness even proved too much for one student, who left the workshop around five minutes into the first exercise. Those of us who bravely remained were introduced to embodiment, through which our perceptions of touch, communication, leadership and trust would be thoroughly rejigged.

Mark Rietema, the somatic movement practitioner who led the workshops for King’s, defines embodiment as ‘the direct, lived, sensory experience of your body’. It is an awareness of the ways in which we live, interact, and experience our immediate environment through our bodies; this includes the relationships we forge with both ourselves and those around us. The more we are aware of our bodies in this way, the more we can understand ourselves, others and our environment a little better as a result.

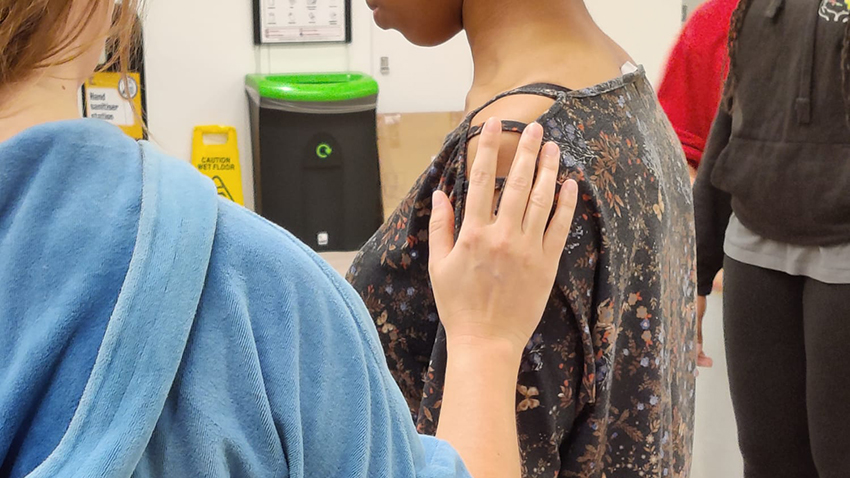

To practice this idea, our group was introduced to contact improvisation, a dance style that focuses on ‘the [improvised] communication between two moving bodies that are in physical contact’ (Contact Quarterly, 2022). The exercises we tried out as a group taught us how to communicate beyond talking, hand gestures and eye contact. Without these tools of communication that we normally rely on, we were quickly forced to listen to the subtle ways in which our bodies engaged in dialogue with one another.

In one exercise we were instructed to link wrists with our partner, and without talking or forcing any movement, begin moving together. Zooming in on one body part initially took a lot of concentration, and it was a task in itself not to force movement as the exercise progressed. But after a couple of minutes, I found myself ‘tuned in’ to the micro movements that my partner made, and soon we were making our way through the room together, navigating the space and bodies around us as we moved.

Tasks like these broke down our group’s feelings of awkwardness and apprehension almost immediately. Without verbally communicating, we got to know each other through our styles of moving. Just like the ‘blind’ exercise I described in the opening paragraph, these contact improvisation techniques shut down our main forms of communication, and instead we turned to physical contact as a way of reading our own bodies, the bodies of others, and the space around us.

Since completing the workshops, I have been thinking about how the concept of embodiment relates to my profession. I work with adults with learning disabilities, autism and mental health needs, so I have the privilege of getting to know individuals who communicate, experience and understand the world around them in ways completely different to my own. My clients have vastly greater challenges than I do in navigating their immediate environment: through sensory sensitivity, physical impairments, and delayed information processing, not to mention the social stigmas and challenges that come with having a disability. So, my question is: how can a greater awareness of your own body as someone with a disability help with the challenges that face you on a daily basis?

In a chat with Mark, we talked about contact improvisation as acknowledging the variety of communication, experiences and physicalities that exist in us. He explained:

“‘It’s this idea of different ways of knowing, and different ways of making sense of the world. It […] challenges in some ways a very cognitive bias, a bias towards making sense of the world only through our very detached thinking.”

Acknowledging that not everyone processes the world in the same way is a critical aspect of embodiment. The practice encourages us to embrace a more ‘feeling’ and less ‘thinking’ process of gaining new knowledge, which in turn recognises the different ways in which the human brain can operate. If more people practised exercises that encouraged these different ways of knowing, we might imagine achieving a more pluralistic society that embraces alternative cognition processes. Practising embodiment can also help us understand how others physically experience their environment through interacting with bodies that function differently to our own.

It is, of course, important to recognise that ‘disabilities’ don’t merely exist within brains and bodies: we live in an environment that is inhospitable to people with physical or cognitive support needs, which makes it challenging for certain individuals to fully take part in society. Mark explains:

“The cultural aspect to embodiment is interesting, because we often think of embodiment as just about our own personal processes, but embodiment happens in a culture that favours particular bodies, particular movements, particular functions. That gives us particular ideas about our own bodies or other people’s bodies as well. By actually stepping into a space of curiosity and humility, it helps us to get a bit of distance from the cultural norms.”

Contact improvisation techniques can actively create a space where bodies are removed from oppressive social barriers: where difference is embraced, playfulness encouraged, and curiosity fostered within a safe environment. Outside of the studio space, it can help highlight the social barriers that exist for people who do not conform to mainstream physical or cognitive expectations. Learning to be comfortable with alternative communication styles is beneficial for everyone; as is getting more in tune with your physical self.

While I might not be practising contact improvisation exercises that involve blindfolding my clients any time soon, I would like to introduce a more ‘embodied’ approach to my interactions with them. This might be through physical ‘check-ins’ in the morning (such as mindful breathing techniques and a good stretch) or breaking up the day with playful dance activities. Simple exercises like these can make us aware of the feelings in our bodies, stay active, acknowledge different communication styles, and – perhaps most importantly – learn to appreciate the joy of movement.

Special thanks to Mark Rietema for taking the time to talk to me for this article.

Written by: Niamh Carey

References:

ARTHEWE – Multiform Pedagogy in Arts, Health and Wellbeing Education, Turku UAS

Contact Quarterly, dance & improvisation journal. About Contact Improvisation (CI)